I suggested that I would try and pull together a thread on some tourbillons, and it kind of turned into a bit of a book, but what the heck, here it is.

I only have one request – I really appreciate the comments and questions, so please go wild, but I hope it isn’t too egotistical of me to hope that this might be a useful reference for some people, so let’s try and have one thread without the pointless, irrelevant, smart ass comments – please.

I have used a lot of online and offline resources, and relied a lot on manufacturer data as well. A big thanks to everyone who makes this info available – there are too many to name them all. All the mistakes are mine alone. I have also shamelessly ‘stolen’ pictures from other websites, but have tried to make sure that none have policies against linking and I thank them all.

OK, let’s start with the basics (somewhat simplified).

A watch movement is basically a system of reduction gears – the minute hand turns 12 (or 24) times faster than the hour hand, the second hand moves 60 times faster than the minute hand, etc – similar to a transmission and differential in a car. And just like in a car you need a motor to drive that motion. In a watch the motor is the escapement which not only converts the fuel (stored energy in the mainspring) into movement, it also serves to ensure that the motion is smooth – no acceleration or deceleration needed in a watch!

The problem is that the escapement is attached to the movement and is therefore subject to movement as the watch moves. That means that the balance wheel which sets the tempo within the escapement has to work with and against external forces – like gravity. This can obviously affect the speed at which the balance wheel vibrates. It’s only a tiny impact, but because of the number of movements it adds up. A Breitling movement is 4 Hz, and 1 Hz is two vibrations (a left and a right). Therefore a Breitling movement has 28,800 moves of the balance wheel every hour – most mechanical watches are 3, 3 ½, 4 or (in the case of the Zenith El Primero) 5 Hz.

When Abraham-Louis Breguet invented the tourbillon (which is French for whirlwind) this motion caused big problems (predominantly in pocket watches in those days) and accuracy was a big problem. The purpose of the tourbillon was to hold the entire escapement within a body (referred to as a cage) that was in constant motion. The tourbillon cage, and hence the escapement was rotated as part of the drive train of the watch and the theory was that this motion helped to counteract the effect of gravity on the escapement. Typically tourbillon cages rotated once a minute, but there is no reason why they had to, some rotated just 10 times an hour. There is some debate about whether a tourbillon actually achieved its purpose, and certainly today it is largely a decorative feature, but that’s what it’s all about.

But this is supposed to be about some of the modern ‘funky’ tourbillons, not a history lesson, so let’s fast forward a couple of centuries, but first off a quick comment on fake tourbillons. The cheap fakes that you see with tourbillon windows are merely showing the balance wheel through the dial – often with a bridge over the top because that’s what most tourbillons need. However there is no rotation of the balance wheel (or any other part of the escapement) – it simply vibrates.

Today, the tourbillon is seen as the ultimate demonstration of a watchmaker’s skill and so companies are constantly trying to outdo themselves by not simply building a tourbillon, but making their tourbillon in a way that no one else can. They’ll usually claim that it helps the watches accuracy, but really – it’s marketing.

So let me start my journey around the world of tourbillons with someone who bucks that trend – Greubel Forsey. Their tourbillons are weird and wonderful at times, but they are designed to be functional – to them a tourbillon has to serve a purpose. This one is an extremely traditional one – a classic tourbillon if you will

What sets it apart is that it’s a 24 second tourbillon – it rotates once every 24 seconds in order to try and really make a difference in accuracy – a wonderful thing to see in motion. That second photo is also through the side of the watch case – so you can get a rare glimpse of a tourbillon from the side. Note that this one is angled relative to the case – something that you can really see from the side

One variation of modern tourbillon is the flying tourbillon. A traditional tourbillon cage is supported from above and below, while the flying tourbillon is cantilevered, with support on only one side. This variation on a tourbillon was invented by a German, Alfred Helwig in 1920. One of the most recent (and best) examples is the Ballon Bleu De Cartier where the Cartier ‘C’ provides the support.

One of the most prolific tourbillon producers these days is Zenith – it sometimes seems like they want to put a tourbillon in everything, and of course they always want to outdo themselves. Enter the Zero G!

This is a multi axis tourbillon, not the first, but certainly the most famous, even though it’s a newcomer. The definition says it all – this tourbillon not just rotates, it also has a gimbal mechanism that ensures that that the balance wheel always remains perfectly flat. There is some debate about whether this is technically a tourbillon, but who cares – it’s a very cool piece of technology.

I don’t want to leave the impression that the Zenith is the only multi axis tourbillon worthy of mention – there are others that are just as incredible, if a little more mainstream. JLC is famous for producing the most affordable Swiss tourbillon (list price under $50,000 in a steel case), but at the other extreme they also have what they call Gyrotourbillons – their take on multi axis. Their gyrotourbillon 1 is an exceptional piece, containing not just a two axis tourbillon, but also a perpetual calendar, an equation of time complication and an 8 day power reserve.

Another way that manufacturers have tried to set themselves apart on tourbillons is to go beyond just one tourbillon. Breguet invented the tourbillon, so it’s fitting to show the double tourbillon by the firm that carries his name.

This piece has two independent tourbillons that not only rotate themselves, they also rotate around the dial, doubling as the hour indicator – so one rotation of the dial every 12 hours.

Greubel Forsey took a different approach to their double tourbillon. They encased a one minute tourbillon inside a four minute tourbillon, offset by 30 degrees

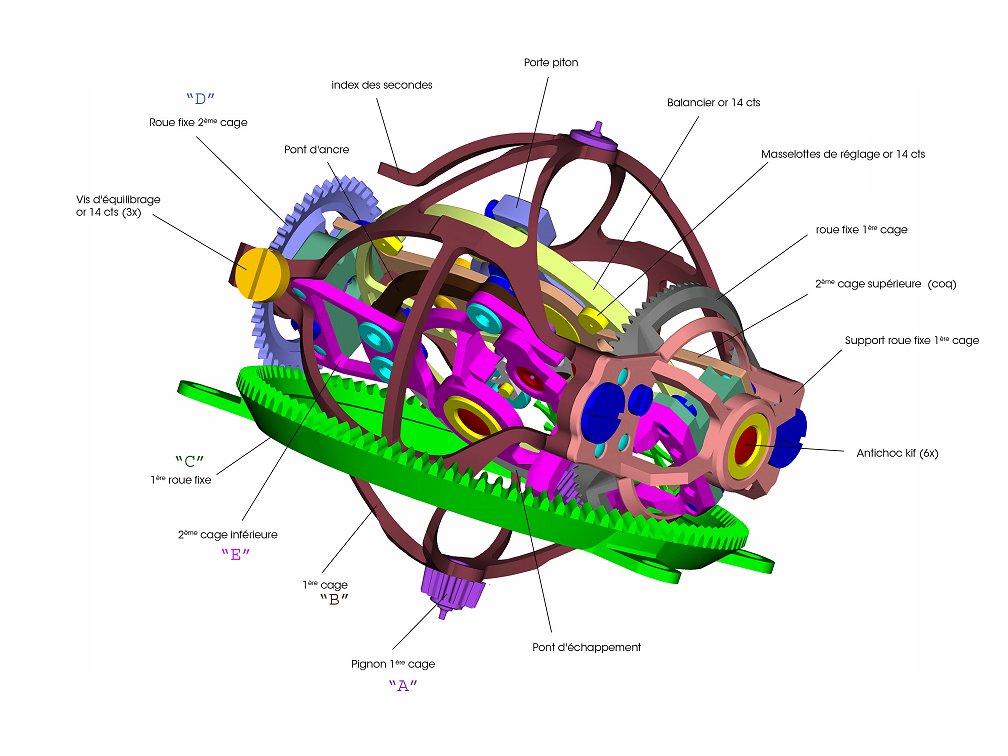

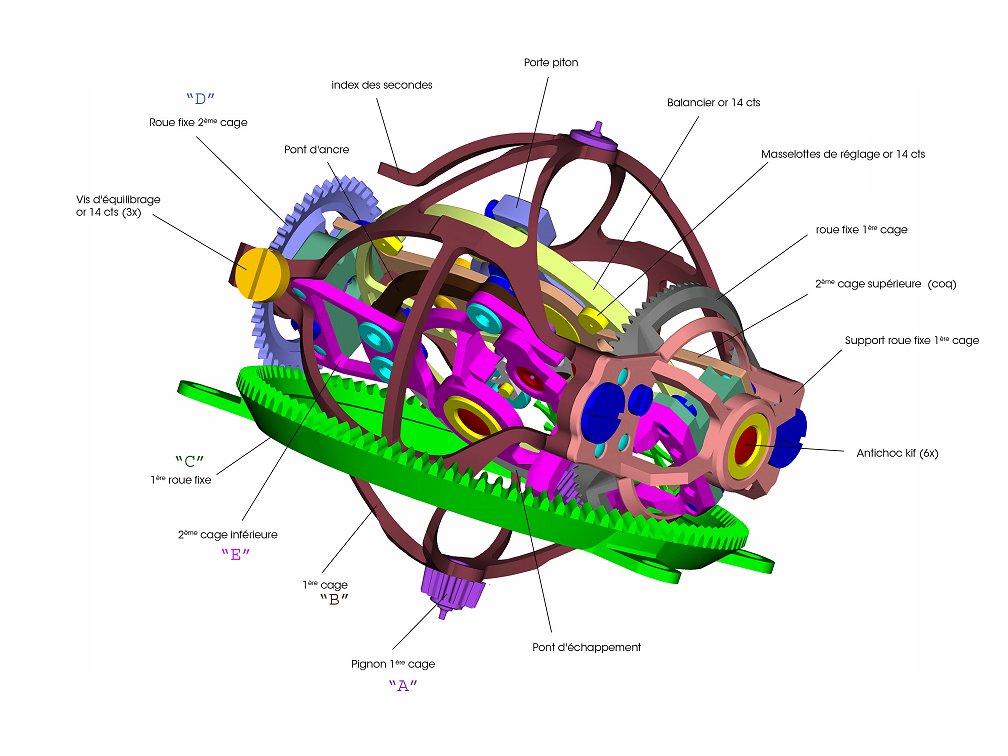

The next watch is the one that started me on a love of tourbillons and haute horlogerie in general. It’s also the watch that interested me in Antoine Preziuso – an interest that is going to cost me a lot of money one day. The 3volution is quite simply incredible.

This watch has three flying tourbillons. Each of these tourbillons rotates within its cage once every minute, and the whole assembly rotates once every 135 seconds. The logic behind this is that the three tourbillons, and the rotation of the assembly work together to compensate one another, creating a natural harmonic resonance.

Let’s finish this where we started – with Greubel Forsey. Maybe the ultimate tourbillon (for now) is their quad tourbillon – four tourbillons in one watch. This takes their double tourbillon concept from above and puts two of them together. While the firm will argue that this is still truly about performance, it’s tough to justify four tourbillons in one watch – this is about showcasing beauty – even down to the sapphire crystal bridges to ensure that everything can truly be seen.

There are many more tourbillons that are worth of mention – if there is enough interest I’ll do a follow up and add some more, and of course Basel 2009 is just weeks away.

I hope that this has been of interest – it’s a different type of post for BreitlingSource, so let’s see what happens. If you’ve got this far then thank you for reading it, and please let me know what you think.